About Haemochromatosis a simple blood test at Dublin Health Screening

Haemochromatosis, or GH (Genetic Haemochromatosis), is a genetic disorder causing the body to absorb an excessive amount of iron from the diet: the iron is then deposited in various organs, mainly the liver, but also the pancreas, heart, endocrine glands, and joints.

Haemochromatosis, or GH (Genetic Haemochromatosis), is a genetic disorder causing the body to absorb an excessive amount of iron from the diet: the iron is then deposited in various organs, mainly the liver, but also the pancreas, heart, endocrine glands, and joints.

Normally the liver stores a small amount of iron for the essential purpose of providing new red blood cells with iron, vital for health. When excessive quantities of iron are stored in the liver it becomes enlarged and damaged. Deposits of iron may also occur in other organs and joints, causing serious tissue damage.

For a long time it was believed that the disorder was rare, so GH was seldom considered as a possible diagnosis. However, recent surveys of people of Northern European origin have shown a prevalence of 1 in 400 likely to be at risk of developing iron overload. GH is now recognised as being one of the most common genetic disorders.

Symptoms

- Chronic fatigue, weakness, lethargy.

- Abdominal pain; sometimes in the stomach region or the upper right-hand side, sometimes diffuse.

- Arthritis; may affect any joint but particularly common in the knuckle and first joint of the first two fingers. The bronze fist (diagram right) – is an arthritic symptom typical of hemochromatosis.

- Diabetes (late onset type).

- Liver disorders; abnormal liver function tests, enlarged liver, cirrhosis.

- Sexual disorders; loss of sex drive, impotence in men, absent or scanty menstrual periods and early menopause in women, decrease in body hair.

- Cardiomyopathy; disease of the heart muscle (not to be confused with disease of the arteries of the heart).

- Neurological/psychiatric disorders; impaired memory, mood swings, irritability, depression.

- Bronzing of the skin, or a permanent tan.

Most of these symptoms are found in other disorders. Chronic fatigue may be ascribed to the after-effects of a viral infection or to psychological causes, and abdominal pain to irritable bowel syndrome. Similarly, liver disorders may be put down to excessive alcohol intake, even in someone who is only a moderate drinker. However, if the above symptoms are present, GH should also be considered as a diagnosis.

Most individuals who have GH will, in due course, develop at least one or two of the above symptoms, although possibly in a very mild form. There may be a long phase of the condition where there are no symptoms. However, if arthritis is found only in the first two finger joints this is highly suggestive of GH.

The need for treatment to remove excess iron does not depend upon the presence of clinical symptoms. The risk of developing a serious complaint such as cirrhosis is much too great to be overlooked.

How is it inherited?

Inherited disorders are caused by defective genes in the cells which make up the body. Genes, which are made of DNA, contain the information the body needs to develop from the egg and to maintain itself in good working order. There are about 30,000 genes and every cell in the body, except sperm and egg cells, contains two copies of each. One of these copies is inherited from the mother and one from the father.

In 1996 the HFE gene was identified as the major gene affected in haemochromatosis. A small change (mutation) is present in both copies of the gene in over 90% of those diagnosed with GH. GH is a ‘recessive’ disorder. The risk of absorbing excess iron will only occur if both copies of the gene are abnormal. If only one copy is defective, an individual will be perfectly healthy but will be a ‘carrier’. This means he or she will be able to pass on the abnormal gene to a son or daughter.

Sperm and egg cells have only one copy of each gene, and on average half the eggs or half the sperm of a carrier will contain the defective version. By contrast, ALL the eggs or sperm of an individual in whom both gene copies are defective and who, as a result, suffers from GH, will carry the abnormal gene.

To develop GH you have to inherit a defective gene from both your parents. This can happen in three ways:

- If both parents are carriers (most common – about 10% of the population are carriers, so 1% of marriages will be between carriers). On average a quarter of the children will develop GH, half will be carriers, and a quarter will be normal.

- If one parent has GH and the other is a carrier (about 1 in 2000 marriages), on average half the children will develop GH, the other half will be carriers.

- If both parents suffer from GH, (a rare event, occurring in about 1 in 100,000 marriages) all the children will inherit two defective genes, and will have GH.

It should be emphasised that the proportions given in examples 1 and 2 are averages for the whole population: in any particular family where both parents are carriers (example 1) it would be possible for all children to be affected, all to be carriers, or for all to be normal.

Relatives who are at risk should be tested. This is absolutely essential in the case of brothers and sisters (siblings) as they stand at least a 1 in 4 chance of being affected. Parents, partners and children from the age of 18, should also be tested.

What are the tests?

- Serum Ferritin

This indicates the amount of iron stored in the body. Levels significantly over 300mcg/l [micrograms per litre] in men and 200æg/l in women are further evidence of GH. It should be realised that in the early stages of iron accumulation, serum ferritin may be within the normal range. Raised TS with a normal serum ferritin level does not rule out a diagnosis of GH.

2. Gene Test

A simple blood test for the HFE gene mutation is positive in over 90% of those affected. It will identify family members at risk of loading iron.

What is the treatment?

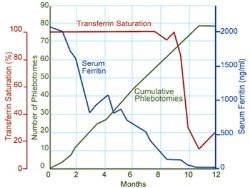

The simple and effective treatment consists of regular removal of blood. Known as venesection therapy or phlebotomy, the procedure is the same as for blood donors. Every pint of blood removed contains a quarter of a gram of iron. The body then uses some of the excess stored iron to make new red blood cells. Venesection will usually be performed once a week, depending on the degree of iron overload. Treatment may need to be continued at this frequency for up to 2 years, occasionally longer.

During the course of treatment, the serum ferritin levels are monitored, indicating the size of the remaining iron stores. Treatment should usually continue until the serum ferritin level reaches 20æg/l (indicating minimal or absent iron stores).

This is not the end of the story. Excess iron will continue to be absorbed so the individual will need occasional venesections (maintenance therapy), on average every 3 to 4 months, for the rest of his or her life. Monitoring of transferrin saturation and serum ferritin is used to assess whether venesection is required more or less often. The transferrin saturation should be maintained below 50% and the serum ferritin below 50mcg/l.

The graph on the right gives an example of how treatment may affect blood iron levels during treatment. Serum ferritin decreases steadily, but transferrin saturation remains high until iron deficiency occurrs, then falls sharply.

How effective is treatment?

Venesection treatment will cause tissue iron to be mobilised and iron stores will return to normal. However, it will not cure some serious clinical conditions such as diabetes or cirrhosis if they are already present at the time treatment is started. This emphasises the need for early diagnosis.

- Fatigue, lethargy and abdominal pain should decrease.

- Cardiomyopathy should improve providing cardiac damage is not severe. In severe cases iron chelation treatment can reverse congestive heart failure.

- Bronzing of the skin should fade.

- Cirrhosis will stay the same.

- Sexual dysfunction and arthritis do not usually improve. Indeed arthritis may appear later even if absent at the time of diagnosis and treatment.

- Providing there is not a massive, long-standing iron overload present at the time treatment is started; those who undergo treatment have a normal life expectancy.

What about diet?

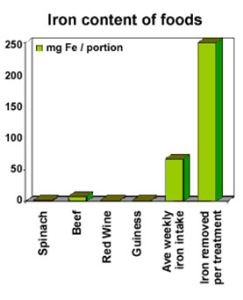

It is not possible to treat GH with a low iron diet. A nutritional natural diet is recommended – the graph on the right illustrates the iron content of a sample of foods, ave

rage weekly intake and the amount of iron removed in each treatment. We make the following recommendations:

+ Avoid vitamin supplements or tonics containing iron, and breakfast cereals heavily fortified with iron. Large doses of vitamin C should also be avoided, as it makes the process of depositing iron in some organs easier and enhances the absorption of iron from the diet.

+ Reduce intake of offal (liver, kidney etc.) and red meat. The rate of iron absorption from red meat is 20 to 30% whereas vegetables and grains have less iron and a 1 to 20% rate of absorption.

+ Minimise alcohol intake, particularly with meals, as it may increase iron absorption and it can also cause liver disease. Tea and all milk products taken with a meal reduce the amount of iron