Vitamin B12 Deficiency Anaemia screen at Dublin Health Screening

A lack of vitamin B12 (‘B12 deficiency’) is one cause of anaemia. Pernicious anaemia is a condition where vitamin B12 cannot be absorbed into your body. It is the most common cause of vitamin B12 deficiency in Ireland. Vitamin B12 deficiency is easily treated by regular injections of vitamin B12.

What is anaemia and vitamin B12 deficiency?

Anaemia means that:

- You have fewer red blood cells than normal, OR

- You have less haemoglobin than normal in each red blood cell.

In either case, a reduced amount of oxygen is carried around in the bloodstream. There are a number of different causes of anaemia (such as lack of iron or certain vitamins).

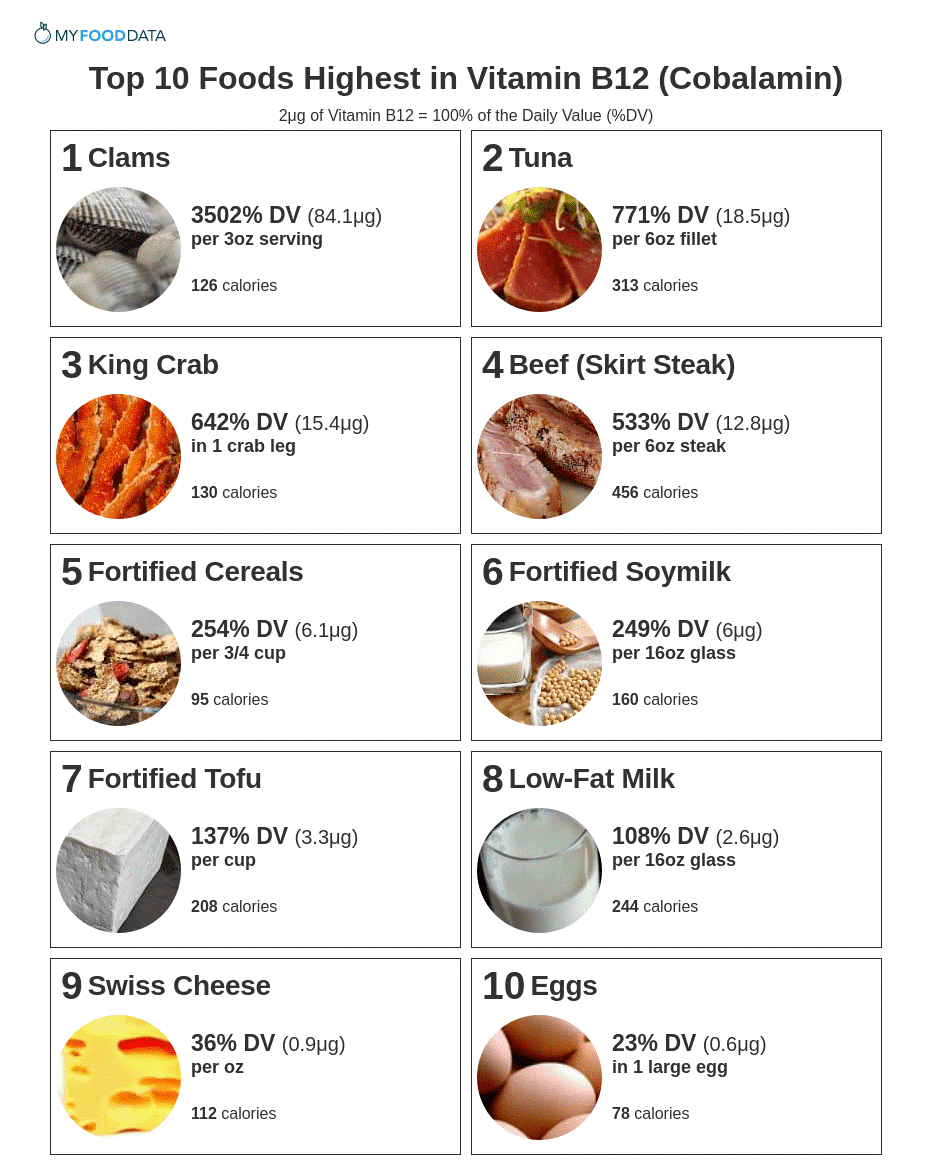

Vitamin B12 is essential for life. It is needed to make new cells in the body such as the many new red blood cells which are made every day. Vitamin B12 is found in meat, fish, eggs, and milk – but not in fruit or vegetables. A normal balanced diet contains enough vitamin B12. A lack of vitamin B12 leads to anaemia and sometimes to other problems.

What are the symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency?

What are the symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency?

Symptoms due to anaemia

These are caused by the reduced amount of oxygen in the body.

- Common symptoms include: tiredness, lethargy, feeling faint, becoming breathless.

- Less common symptoms include: headaches, palpitations, altered taste, being ‘off your food’, and ringing in the ears (tinnitus).

- You may look pale.

Other symptoms

Cells in other parts of the body may be affected if you lack vitamin B12. Other symptoms that may occur include a sore mouth and tongue. If left untreated, problems with nerves can develop. For example: confusion, numbness and unsteadiness. These are uncommon as treatment is usually started when the anaemia is found, and before nerve problems develop.

What are the causes of vitamin B12 deficiency?

Pernicious anaemia

Normally, when you eat foods with vitamin B12, the vitamin combines with a protein called intrinsic factor in the stomach. The combined vitamin B12/intrinsic factor is then absorbed into the body further down the gut at the end of the small intestine. (Intrinsic factor is made by cells in the lining of the stomach and is needed for vitamin B12 to be absorbed.)

Pernicious anaemia is the most common cause of B12 deficiency in Ireland. It is due to an ‘autoimmune disease’. The immune system normally makes antibodies to attack bacteria, viruses and other ‘germs’. If you have an autoimmune disease, the immune system makes antibodies against certain tissues of your body. If you have pernicious anaemia, antibodies are formed against your intrinsic factor, or against the cells in your stomach which make intrinsic factor. This stops intrinsic factor from attaching to vitamin B12, and so the vitamin cannot be absorbed into your body. It is thought that something triggers the immune system to make antibodies against intrinsic factor. The ‘trigger’ is not known.

Pernicious anaemia usually develops over the age of 50. Women are more commonly affected than men, and it tends to run in families. It occurs more commonly in people who have other autoimmune diseases such as thyroid diseases, Addison’s disease and vitiligo. The antibodies which cause pernicious anaemia can be detected by a blood test to confirm the diagnosis.

Stomach or gut problems

Various problems of the stomach or gut can be a cause of B12 deficiency. They are all uncommon causes. They include:

- Surgery to remove the stomach or the end of the small intestine. This will mean absorption of vitamin B12 may not be possible.

- Some diseases that affect the end of the small intestine where vitamin B12 is absorbed may affect the absorption of the vitamin. For example, Crohn’s disease.

- Some conditions of the stomach may affect the production of intrinsic factor which is needed to combine with vitamin B12 to be absorbed. For example, atrophic gastritis (where the lining of the stomach is ‘thinned’).

Drugs

Certain drugs used for other conditions may affect the absorption of vitamin B12. The most common example is metformin which is a drug commonly used for diabetes. Other drugs include: colchicine, neomycin, and some anticonvulsants used to treat epilepsy.

Note: long-term use of drugs that affect stomach acid production such as H2 blockers and proton pump inhibitors can worsen B12 deficiency. This is because stomach acid is needed to release vitamin B12 bound to proteins in food. However, such drugs are not causes of B12 deficiency.

Dietary causes

It is unusual to lack vitamin B12 if you eat a normal balanced diet. Strict vegans who take no animal or dairy produce may not eat enough vitamin B12.

What is the treatment for vitamin B12 deficiency?

You will need vitamin B12 injections. About six injections are given at first, one every 2-4 days. This quickly builds up the body’s store of vitamin B12. Vitamin B12 is stored in the liver. Once a store of vitamin B12 is built up, this can supply the body’s needs for several months. An injection is then only needed every three months to top up the supply.

If you have pernicious anaemia the injections are needed for life. You should have no side-effects from the treatment as it is simply replacing a vitamin that you need. If the cause of your lack of vitamin B12 is diet related rather than due to pernicious anaemia then treatment may be different. That is, after the initial treatment with injections of B12, dietary supplements of B12 (cyanocobalamin tablets) may be advised instead of injections.

Oysters and clams are surpassed only by liver as good sources of Vitamin B 12

Know your Lung function.

What is a spirometer and spirometry?

What is a spirometer and spirometry?

A spirometer is a device which measures the amount of air that you can blow out. There are various spirometer devices made by different companies, but they all measure the same thing. They all have a mouthpiece that you use to blow into the device.

How is it done?

You breathe in fully and then seal your lips around the mouthpiece of the spirometer. You then blow out as fast and as far as you can until your lungs are completely empty. This can take several seconds. You may also be asked to breathe in fully and then breathe out slowly as far as you can.

A clip may be put onto your nose to make sure that no air escapes from your nose. The above routine may be done two or three times to check that the readings are much the same each time you blow into the machine.

What does the spirometer measure?

The most common measurements used are:

- FEV1 – Forced Expiratory Volume in one second. This is the amount of air you can blow out within one second. With normal lungs and airways you can normally blow out most of the air from your lungs within one second.

- FVC – Forced Vital Capacity. The total amount of air that you blow out in one breath.

- FEV1 divided by FVC (FEV1/FVC). Of the total amount of air that you can blow out in one breath, this is the proportion that you can blow out in one second.

What can the measurements show?

A spirometry reading usually shows one of four main patterns:

- Normal

- An obstructive pattern

- A restrictive pattern

- A combined obstructive / restrictive pattern

Normal

Normal readings vary, depending on your age, size, and sex. The range of normal readings are published on a chart.

An obstructive pattern – typical of diseases that cause narrowed airways

If your airways are narrowed, then the amount of air that you can blow out quickly is reduced. So, your FEV1 is reduced and the ratio FEV1/FVC is lower than normal. As a rule, you are likely to have a disease that causes narrowed airways if:

- your FEV1 is less than 80% of the predicted value for your age, sex and size, or

- your FEV1/FVC ratio is 0.7 or less.

However, with narrowed airways, the total capacity of your lungs is often normal or only mildly reduced. So, with an obstructive pattern the FVC is often normal or near normal.

The main conditions that cause narrowing of the airways and an obstructive pattern of spirometry are asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). So, spirometry can help to diagnose these conditions. Spirometry can also help to assess if treatment (inhalers etc) ‘open up’ the airways as the readings will improve if the narrowed airways become wider. As a guide, the following values help to diagnose COPD and its severity:

- COPD unlikely – FEV1 is 80% or more of the predicted value for your age, size and sex

- Mild airflow obstruction – FEV1 is 50-80% of the predicted value

- Moderate airflow obstruction – FEV1 is 30-49% of the predicted value

- Severe airflow obstruction – FEV1 is 30% or less of the predicted value

A restrictive pattern – typical of certain lung diseases

With a restrictive spirometry pattern your FVC is less than the predicted value for your age, sex and size. This is caused by various conditions that affect the lung tissue itself, or affect the capacity of the lungs to expand and hold a normal amount of air. For example, conditions that cause fibrosis or scarring of the lung such as pneumoconiosis. Or, a physical deformity that restricts the expansion of the lungs. Your FEV1 is also reduced but this is in proportion to the reduced FVC. So, with a restrictive pattern the ratio of FEV1/FVC is normal.

A combined obstructive / restrictive pattern

With this you may have two conditions, for example, asthma plus another lung disorder. Also, some lung conditions have features of both an obstructive and restrictive pattern. For example, with cystic fibrosis there is a lot of mucus in the airways which causes narrowed airways, and damage to the lung tissue may also occur.

Is spirometry the same as peak flow readings?

No. A peak flow meter is a small device that measures the fastest rate of air that you can blow out of your lungs. Like spirometry, it can detect airways narrowing. It is more convenient than spirometry and is commonly used to help diagnose asthma. Many people with asthma also use a peak flow meter to monitor their asthma. For people with COPD, a peak flow reading may be useful to give a rough idea of airways narrowing, but it can underestimate the severity of COPD. Therefore, spirometry is a more accurate test for diagnosing and monitoring people with COPD.

What preparation is needed before having spirometry?

The instructions include such things as not to use a bronchodilator inhaler for a set time before the test (several hours or more, depending on the inhaler). Also, not to have alcohol, a heavy meal, or do vigorous exercise for a few hours before the test. Ideally, you should not smoke for 24 hours before the test.

Smear Tests

Smear tests for women are provided for free as part of the health screen as our doctors are fully registered with cervical check see below. Note we have a turnaround time of 2 weeks on these results.

The following questions are most commonly asked by women attending for their free smear test:

About Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer is a cancer of the cells of the cervix (neck of the womb). Cervical cancer is the second most common female cancer in Europe. Cervical cells change slowly and take many years to develop into cancer cells, making cervical cancer a preventable disease.

How can I reduce my risk of getting cervical cancer?

-Have a regular smear test to pick up any early problems.

-Stop smoking

-Visit your doctor if you have any concerns or symptoms such as irregular vaginal bleeding, spotting or discharge.

How is a smear test taken?

A smear test is a very simple procedure that takes less than five minutes. It may be slightly uncomfortable but should not be painful.

You may lie on your side or on your back for your smear test. The doctor or nurse taking the test will gently insert an instrument called a speculum into your vagina to hold it open. The cervix is the area where the top of the vagina leads to the uterus (womb). The doctor or nurse will use a small, specialised brush to gently remove a sample of cells from the cervix. This sample is sent to the laboratory to be checked.

How often should I have a smear test?

After the first smear test, women aged 25 to 44 will be invited by CervicalCheck to have a free smear test every three years. We will invite women aged 45 to 60 to have a free smear test every five years once they have had two ‘no abnormality detected’ smear test results at three yearly intervals.

CervicalCheck will advise you when your next free smear test is due. If you have any unusual or irregular vaginal bleeding, spotting or discharge, do not wait for your next smear test – contact your doctor immediately.

How will CervicalCheck use my information?

We will use your details to:

-invite you for a free CervicalCheck smear when your test is due

-advise you if any further treatment is needed or when to have your next smear test

-include in statistics and reports – this will help to review CervicalCheck and find out how well it is working

-possibly invite you to take part in research

Is consent necessary?

A woman is asked to sign a consent form prior to her free smear test. This consent allows CervicalCheck to receive, hold and use a woman’s personal details and information about her smear test sample. This may include past smear samples and colposcopy results.

CervicalCheck may share this information with the doctor or nurse who took your smear test (smeartaker), laboratory staff, colposcopy clinic, the National Cancer Registry and their servants or agents.

Results

CervicalCheck will send you a letter about your results within four weeks of your smear test. The result of your test will also be available from your smeartaker.

Most smear test results are found to be normal. Please try not to worry if you are called back for another test. The result could be due to an infection or minor cells changes that may or may not need treatment.

If your result is not normal you may need to have another free smear test or a more detailed examination of the cervix using a type of microscope. This test is called a colposcopy. If there are cell changes on your cervix they can be easily treated to prevent them developing into cancer cells.

What if I’ve had a hysterectomy?

If you have had a hysterectomy, you should check with your doctor to see if you need to continue having regular smear tests. In general, the need to screen after a hysterectomy will depend on whether you have a cervix.

What is a colposcopy?

A colposcopy is a simple examination that is carried out the same way as a smear test. A doctor or nurse will look at the cervix using a type of microscope called a colposcope. During the examination, a liquid or dye may be applied to the cervix to help identify any changes to the cells. A colposcopy can be done safely during pregnancy.

Before the colposcopy, the doctor or nurse should explain:

-the colposcopy examination,

-the possible treatments for changes in the cells of the cervix, and

-any risks linked to the treatment.

What is a smear test?

A smear test (sometimes called a pap test) is used for cervical screening. It is a simple procedure where a doctor or nurse (smeartaker) takes a sample of cells from the cervix (neck of the womb) to look for early changes. A smear test can identify cell changes before they become cancer cells. If these cells are not found and treated, they could become cancerous.

What is cervical screening?

Cervical screening tests women for changes in the cells of the cervix (neck of the womb) by a smear test.

What is CervicalCheck?

CervicalCheck – The National Cervical Screening Programme is a Government-funded service that provides free smear tests to women aged 25 to 60.

What is the CervicalCheck register?

The CervicalCheck register is a secure electronic database that contains your name, address, date of birth and Personal Public Service Number (PPS No.). The register also records your smear test results and any related procedures that you might have had.

Be assured that your information is secure. To maintain confidentiality, you will be given a unique identification number by the CervicalCheck register. You can make sure you are on the register by calling CervicalCheck on Freephone 1800 45 45 55 or checking online at www.cervicalcheck.ie. To keep the register up to date, please let us know if there is any change to your personal details such as name or address.

The Health (Provision of Information) Act 1997 allows CervicalCheck get your name, address and date of birth so that we can invite you for regular free smear tests.

When is the best time to have a smear test?

The best time to attend for your smear test is mid-cycle – that is, 10 to 14 days after the first day of your period (if you are having periods).

Where can I have a smear test?

You can choose to have a free smear test from any smeartaker (doctor or nurse) registered with CervicalCheck. For example:

-General Practitioners (GPs) and practice nurses,

-Family Planning Clinics, and

-Well Woman Centres or Women’s Health Clinics.

Who should have a smear test?

Every woman aged between 25 and 60 should have a regular smear test and continue to have regular smear tests after the menopause. If you are aged over 60 years and have never had a smear test, please contact your local CervicalCheck registered smeartaker to discuss your cervical screening needs.

Why should I have this test?

Quite simply, having a regular smear test could save your life.

Routine Blood work up at Dublin Health Screen to include renal function, liver function and inflammatory markers

Blood can be tested for many different things. The person who requests the blood test will write on the form which tests they want the ‘lab’ to do. Different blood bottles are used for different tests. For example, for some tests the blood needs to clot and the test is looking for something in serum. For some tests, the blood is added to some chemicals to prevent it from clotting. If the blood glucose is being measured, then the blood is added to a special preservative, etc. This is why you may see your blood added to blood bottles of different sizes and colours. In the case of a health screen then the largest range of bloods possible are taken.

Blood tests are taken for many different reasons, for example, to:

- Help diagnose certain conditions, or to rule them out if symptoms suggest possible conditions.

- Monitor the activity and severity of certain conditions. For example, a blood test may help to see if a condition is responding to treatment.

- Check the body’s functions such as liver and kidney function when you are taking certain medicines which may cause side-effects.

- Check your blood group before receiving a blood transfusion.

The standard blood tests at Dublin health screen are as follows,

- Full blood count – checks for anaemia, and other conditions which affect the blood cells.

- Blood chemistry.

- Kidney function.

- Liver function.

- Hormone levels.

- Blood glucose (sugar) level.

- Tests for inflammation.

- Blood cholesterol level.

- To check the levels of certain medicines to ensure you are taking the correct dose.

- Immunology – such as checking for antibodies to certain viruses and bacteria.

What is normal blood made up of?

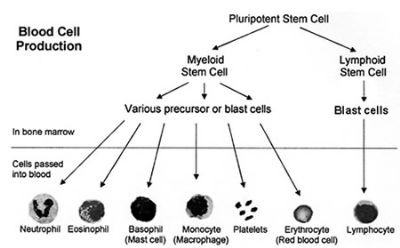

Blood cells, which can be seen under a microscope, make up about 40% of the blood’s volume. Blood cells are divided into three main types:

-

- Red cells (erythrocytes). These make blood a red colour. One drop of blood contains about five million red cells. A constant new supply of red blood cells is needed to replace old cells that break down. Millions of red blood cells are made each day. Red cells contain a chemical called haemoglobin. This binds to oxygen, and takes oxygen from the lungs to all parts of the body.

- White cells (leucocytes). There are different types of white cells which are called neutrophils (polymorphs), lymphocytes, eosinophils, monocytes, and basophils. They are part of the immune system. Their main role is to defend the body against infection.

- Platelets. These are tiny and help the blood to clot if we cut ourselves.

- Plasma is the liquid part of blood and makes up about 60% of the blood’s volume. Plasma is mainly made from water, but also contains many different proteins and other chemicals such as hormones, antibodies, enzymes, glucose, fat particles, salts, etc.

When blood spills from your body (or a blood sample is taken into a plain glass tube) the cells and certain plasma proteins clump together to form a clot. The remaining clear fluid is called serum.

Bone marrow

Blood cells are made in the bone marrow by ‘stem’ cells. The bone marrow is the soft ‘spongy’ material in the centre of bones. The large flat bones such as the pelvis and breast-bone (sternum) contain the most bone marrow. To constantly make blood cells you need a healthy bone marrow. You also need nutrients from your diet including iron and certain vitamins.

Stem cells

Stem cells are primitive (immature) cells. There are two main types in the bone marrow – myeloid and lymphoid stem cells. These derive from even more primitive common ‘pleuripotent’ stem cells. Stem cells constantly divide and produce new cells. Some new cells remain as stem cells and others go through a series of maturing stages (‘precursor’ or ‘blast’ cells) before forming into mature blood cells. Mature blood cells are released from the bone marrow into the bloodstream.

- Lymphocyte white blood cells develop from lymphoid stem cells. There are three types of mature lymphocytes:

- B lymphocytes make antibodies which attack infecting bacteria, viruses, etc.

- T lymphocytes help the B lymphocytes to make antibodies.

- Natural killer cells which also help to protect against infection.

- All the other different blood cells (red blood cells, platelets, neutrophils, basophils, eosinophils and monocytes) develop from myeloid stem cells.

Blood production

You make millions of blood cells every day. Each type of cell has an expected life-span. For example, red blood cells normally last about 120 days. Some white blood cells last just hours or days – some last longer. Every day millions of blood cells die and are broken down at the end of their life-span. There is normally a fine balance between the number of blood cells that you make, and the number that die and are broken down. Various factors help to maintain this balance. For example, certain hormones in the bloodstream, and chemicals in the bone marrow called ‘growth factors’, help to regulate the number of blood cells that are made.

What is a blood group?

Red blood cells have certain proteins on their surface called antigens. Also, your plasma contains antibodies which will attack certain antigens if they are present. There are various types of red blood cell antigens – the ABO and rhesus types are the most important.

ABO types

These were the first type discovered.

- If you have type A antigens on the surface of your red blood cells, you also have anti-B antibodies in your plasma.

- If you have type B antigens on the surface of your red blood cells, you also have anti-A antibodies in your plasma.

- If you have type A and type B antigens on the surface of your red blood cells, you do not have antibodies to A or B antigens in your plasma.

- If you have neither type A or type B antigens on the surface of your red blood cells, you have anti-A and anti-B antibodies in your plasma.

Rhesus types

Most people are ‘rhesus positive’ as they have rhesus antigens on their red blood cells. But, about 3 in 20 people do not have rhesus antibodies and are said to be ‘rhesus negative’.

Blood group names

Your ‘blood group’ depends on which antigens occur on the surface of your red blood cells. Your blood group is said to be:

- A+ (A positive) if you have A and rhesus antigens.

- A– (A negative) if you have A antigens, but not rhesus antigens.

- B+ (B positive) if you have B and rhesus antigens.

- B– (B negative) if you have B antigens, but not rhesus antigens.

- AB+ (AB positive) if you have A, B and rhesus antigens.

- AB– (AB negative) if you have A and B antigens, but not rhesus antigens.

- O+ (O positive) if you have neither A nor B antigens, but you have rhesus antigens.

- O– (O negative) if you have do not have A, B or rhesus antigens.

Other blood types

There are many other types of antigen which may occur on the surface of red blood cells. However, most are classed as ‘minor’ and are not as important as ABO and rhesus.

How does blood clot?

Within seconds of cutting a blood vessel, the damaged tissue causes platelets to become ‘sticky’ and clump together around the cut. These ‘activated’ platelets and the damaged tissue release chemicals which react with other chemicals and proteins in the plasma called ‘clotting factors’. There are 13 known clotting factors which are called by their Roman numbers – factor I to factor XIII. A complex cascade of chemical reactions involving these clotting factors quickly occurs next to a cut. The final step of this cascade of chemical reactions is to convert factor I (also called fibrinogen – a soluble protein) into thin strands of a solid protein called fibrin. The strands of fibrin form a meshwork, and trap blood cells and platelets so that a solid clot is formed.

If a blood clot forms within a healthy blood vessel it can cause serious problems. So, there are also chemicals in the blood which prevent clots from forming, and chemicals which ‘dissolve’ clots. So, there is a balance between forming clots and preventing clots. Normally, unless a blood vessel is damaged or cut, the ‘balance’ tips in favour of preventing clots forming within blood vessels.

Some types of blood disorders

Problems with blood cells

- Anaemia means that you have less red blood cells than normal, or have less haemoglobin than normal in each red blood cell. There are many causes of anaemia. For example, the most common cause of anaemia in the UK is a lack of iron. (Iron is needed to make haemoglobin.) Other causes include lack of vitamins B12 or folate which are needed to make red blood cells. Abnormalities of red blood cell production can cause anaemia. For example, various hereditary conditions such as sickle cell disease and thalassaemia.

- Too many red cells is called polycythaemia and can be due to various causes.

- Too few white cells is called leucopenia. Depending on which type of white cell is reduced it can be called neutropenia, lymphopenia, or eosinopenia. There are various causes.

- Too many white blood cells is called leucocytosis. Depending on which type of white cell is increased it is called neutrophilia, lymphocytosis, eosinophilia, monocytosis, basophilia. There are various causes. For example:

- various infections can cause an increase of white blood cells.

- certain allergies can cause an eosinophilia.

- leukaemia causes a large increase in the number of white blood cells. The type of leukaemia depends on the type of white cell affected.

- Too few platelets which is called thrombocytopenia. This may make you bruise or bleed easily. There are various causes.

- Too many platelets which is called thrombocythaemia. This is due to disorders which affect cells in the bone marrow which make platelets.

Bleeding disorders

There are various conditions where you tend to bleed excessively if you damage or cut a blood vessel. For example:

- Too few platelets (thrombocytopenia) – due to various causes.

- Genetic conditions where you do not make one or more clotting factors. The most well known is haemophilia A which occurs in people who do not make factor VIII.

- Lack of vitamin K can cause bleeding problems as you need this vitamin to make certain clotting factors.

- Liver disorders can sometimes cause bleeding problems as your liver makes most of the clotting factors.

Clotting disorders

Sometimes a blood clot forms within a blood vessel which has not been injured or cut. For example:

- A blood clot which forms within a coronary (heart) artery or in an artery within the brain is the common cause of heart attack and stroke. The platelets become sticky and clump next to patches of atheroma (fatty material) in blood vessels and activate the clotting mechanism.

- Sluggish blood flow can make blood clot more readily than usual. This is a factor in deep vein thrombosis (DVT) which is a blood clot that sometimes forms in a leg vein.

- Certain genetic conditions can make the blood clot more easily than usual.

- Certain medicines can affect the blood clotting mechanism, or increase the amount of some clotting factors, which may result in the blood clotting more readily.

- Liver disorders can sometimes cause clotting problems as your liver makes some of the chemicals involved in preventing and dissolving clots.

Prostate screen is a simple blood test

Should I be screened for prostate cancer?

Men who are screened run some risks from the biopsy test, and may not benefit from treatment even if they do have cancer. In fact, by diagnosing and treating cancers that might not need to be treated, the risk of reduced quality of life from treatment complications may be higher than if they were not screened. This does not stop men asking to be screened and a test (the PSA test) is available as a standard blood test at Dublin Heath screen. You may know or have heard of someone who swears by the PSA test (for more on this see Screening tests heading below). However, there are a number of factors that mean the test would not be helpful to everyone. Right now, there is no evidence that screening a man without symptoms will help him to live longer.

Men who are screened run some risks from the biopsy test, and may not benefit from treatment even if they do have cancer. In fact, by diagnosing and treating cancers that might not need to be treated, the risk of reduced quality of life from treatment complications may be higher than if they were not screened. This does not stop men asking to be screened and a test (the PSA test) is available as a standard blood test at Dublin Heath screen. You may know or have heard of someone who swears by the PSA test (for more on this see Screening tests heading below). However, there are a number of factors that mean the test would not be helpful to everyone. Right now, there is no evidence that screening a man without symptoms will help him to live longer.

If you feel well but have some concerns about prostate cancer, or if you have symptoms, a discussion of the options will help you decide on a course of action. The things to be considered are any family history of cancer, your age, your general health and how a diagnosis of cancer may affect you. Dublin Health screen can advise you of the potential risks and benefits of being screened, and also of the treatment options for cancer if it was to be detected. It is possible that you might not be seriously affected, even if you have cancer. Possible symptoms include difficulty starting to pass urine, a slow flow, dribbling, blood in the urine, having to get up often at night, or having to rush to get to the toilet. Remember that these symptoms can be caused by a number of medical problems.

What is prostate cancer?

Prostate cancer is a cancer that develops in the prostate gland. The prostate sits just below the bladder and is about the size of a walnut. Problems begin when the gland grows bigger, which commonly happens as you get older. Half of all men over 50 have enlargement of the prostate gland. Only one in 10 men with prostate symptoms will have cancer; in the rest, the cause of symptoms is usually a non-cancerous enlargement known as benign prostatic hypertrophy. Benign enlargement of the prostate gland tends to occur at the same age as prostate cancer, but there is no evidence that one leads to another. Prostate cancer is one of the most common causes of death from cancer in Irish men. Every year about 2000 to 3000 cases of prostate cancer is diagnosed, three quarters in men over 70. About 500 men die from the disease every year, nearly half of them over 80 years old. The figures are not as worrying as they seem. More men who have been diagnosed as having prostate cancer die from other causes than die from the cancer itself. However, it is difficult, even with screening, to identify tumours that are going to develop rapidly.

What screening tests for prostate cancer are available at Dublin health screen?

The term screening refers to tests that pick-up disease at an early stage. The most common test for prostate cancer is the PSA test, which measures a substance called Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) in the blood. PSA is a normal product of the prostate gland, but raised levels suggest cancer or other prostate problems. Doctors looking for prostate cancer will do a PSA test in conjunction with a rectal examination of the prostate gland itself. If the PSA test is positive, other tests and investigations will have to be done before a definite diagnosis of cancer can be made. This usually requires an ultrasound test and a needle biopsy of the prostate gland. Three quarters of men who have a positive PSA test will not have cancer, so the PSA test is not itself a reliable diagnosis. There is also a small risk of infection and bleeding from a biopsy, so the test is only done if there is a suspicion that a cancer is present.

How is prostate cancer treated?

The main ways to treat prostate cancer that has not spread are either radical surgery to remove the whole prostate gland (radical prostatectomy) or radiotherapy. Because both forms of treatment carry significant risk of complications like impotence, incontinence and bowel problems, ‘watchful waiting’ can be considered as an alternative option. The current evidence is that treating some prostate cancers does not improve your likelihood of survival, and may reduce the quality of your remaining life.

High Blood Pressure (Hypertension) screen at Dublin Health Screening

High Blood Pressure (Hypertension) screen at Dublin Health Screening

Having high blood pressure is one of several ‘risk factors’ that can increase your chance of developing heart disease, a stroke, and other serious conditions. As a rule, the higher the blood pressure, the greater the risk. Treatment includes a change in lifestyle risk factors where these can be improved – losing weight if you are overweight, regular physical activity, a healthy diet, cutting back if you drink a lot of alcohol, stopping smoking, and a low salt intake. If needed, medication can lower blood pressure.

What is blood pressure?

Blood pressure is the pressure of blood in your arteries (blood vessels). Blood pressure is measured in millimetres of mercury (mmHg). Your blood pressure is recorded as two figures. For example, 150/95 mmHg. This is said as ‘150 over 95’.

- The top (first) number is the systolic pressure. This is the pressure in the arteries when the heart contracts.

- The bottom (second) number is the diastolic pressure. This is the pressure in the arteries when the heart rests between each heartbeat.

What is high blood pressure?

High blood pressure is a blood pressure that is 140/90 mmHg or above each time it is taken. That is, the blood pressure is ‘sustained’ at 140/90 mmHg or above. High blood pressure can be:

- just a high systolic pressure, for example, 170/70 mmHg.

- just a high diastolic pressure, for example, 120/104 mmHg.

- or both, for example, 170/110 mmHg.

However, it is not quite as simple as this. Depending on various factors, the level at which blood pressure is considered high enough to be treated with medication can vary from person to person.

Blood pressure of 160/100 mmHg or above

This is definitely high. All people with a blood pressure that stays at this level are usually offered medication to lower it (described later).

Blood pressure of 140/90 mmHg or above but below 160/100 mmHg

This is sometimes called ‘mild’ high blood pressure. Ideally, it should be lower than this but for many people the risk from mild high blood pressure is small, and drug treatment is not indicated. However, certain groups of people with blood pressure in this range are advised medication to lower it. These are people with:

- a high risk of developing cardiovascular diseases (see below), or

- an existing cardiovascular disease (see below), or

- diabetes, or

- damage to the heart or kidney (organ damage) due to high blood pressure.

Blood pressure between 130/80 and 140/90 mmHg

For most people this level is fine. However, current UK guidelines suggest that this level is too high for certain groups of people. Treatment to lower your blood pressure if it is 130/80 mmHg or higher may be considered if you:

- Have developed a complication of diabetes, especially kidney problems.

- Have had a serious cardiovascular event such as a heart attack, TIA or stroke.

- Have certain chronic (ongoing) kidney diseases.

How is high blood pressure diagnosed at Dublin health Screen?

A one-off blood pressure reading that is high does not mean that you have ‘high blood pressure’. Your blood pressure varies throughout the day. It may be high for a short time if you are anxious, stressed, or have just been exercising.

You are said to have ‘high blood pressure’ (hypertension) if you have several blood pressure readings that are high, and which are taken on different occasions, and when you are relaxed.

Observation period

If one reading is found to be high, it is usual for your doctor or nurse to advise a time of observation. This means several blood pressure checks at intervals over time. The length of the observation period varies depending on the initial reading, and if you have other health risk factors. However depending on the reading we are also able to arrange a 24 hour Holter BP monitor which will measure will take around 40 readings of your BP over 24. We will attach same at the practice and you are allowed go home 24 hours later you return to the practice and the results are fed into a computer. You will find out then if you have definite hypertension or if you have a syndrome called white coat syndrome.

One reason this may be advised is because some people become anxious in medical clinics which can cause the blood pressure to rise. (This is called ‘white coat’ hypertension.) Home or ambulatory monitoring of blood pressure may show that the blood pressure is normal when you are relaxed.

Above is a the Holter bp monitor used at Dublin Health Screening.

What causes high blood pressure?

The cause is not known in most cases

This is called ‘essential hypertension’. The pressure in the arteries depends on how hard the heart pumps, and how much resistance there is in the arteries. It is thought that slight narrowing of the arteries increases the resistance to blood flow, which increases the blood pressure. The cause of the slight narrowing of the arteries is not clear. Various factors probably contribute.

In some cases, high blood pressure is caused by other conditions

It is then called ‘secondary hypertension’. For example, certain kidney or hormone problems can cause high blood pressure.

How common is high blood pressure?

In Ireland, about half of people over 65, and about 1 in 4 middle aged adults, have high blood pressure. It is less common in younger adults. Most cases are mildly high (up to 160/100 mmHg). However, at least 1 in 20 adults have blood pressure of 160/100 mmHg or above. High blood pressure is more common in people:

- with diabetes. About 3 in 10 people with Type 1 diabetes and more than half of people with Type 2 diabetes eventually develop high blood pressure.

- from African-Caribbean origin.

- with a family history of high blood pressure.

- with certain lifestyle factors. That is, those who: are overweight, eat a lot of salt, don’t eat many fruit and vegetables, don’t take enough exercise, or drink a lot of alcohol.

Do I need any tests?

If you are diagnosed as having high blood pressure then you are likely to be examined by one of our doctors and have some routine tests which include:

- A urine test to check if you have protein or blood in your urine which is done as standard at the Dublin health screen.

- A blood test to check that your kidneys are working fine, and to check your cholesterol level and sugar (glucose) level again standard at the screen

- A heart tracing (an electrocardiogram, also called an ECG) finally again standard.

The purpose of the examination and tests is to:

- Rule out (or diagnose) a ‘secondary’ cause of high blood pressure such as kidney disease.

- To check to see if the high blood pressure has affected the heart.

- To check for other ‘risk factors’ such as a high cholesterol level or diabetes (see below).

Who should have a blood pressure check?

High blood pressure usually causes no symptoms. You will not know if you have high blood pressure unless you have your blood pressure checked. Therefore, everyone should have regular blood pressure checks at least every 3-5 years. The check should be more often (at least once a year) in: older people, people who have had a previous high reading, people with diabetes, and people who have had a previous reading between 130/85 and 139/89 mmHg (that is, not much below the ‘cut off’ point for high blood pressure).

Why is high blood pressure a problem if it causes no symptoms?

High blood pressure is a ‘risk factor’ for developing a cardiovascular disease (such as a heart attack or stroke), and kidney damage, sometime in the future. If you have high blood pressure, over the years it may have a damaging effect to arteries and put a strain on your heart. In general, the higher your blood pressure, the greater the health risk. But, high blood pressure is just one of several possible risk factors for developing a cardiovascular disease.

What are cardiovascular diseases?

Cardiovascular diseases are diseases of the heart (cardiac muscle) or blood vessels (vasculature). However, in practice, when doctors use the term ‘cardiovascular disease’ they usually mean diseases of the heart or blood vessels that are caused by atheroma. Patches of atheroma are like small fatty lumps that develop within the inside lining of arteries (blood vessels). Atheroma is also known as ‘atherosclerosis’ and ‘hardening of the arteries’.

Risk factors

Everybody has some risk of developing atheroma which may cause one or more cardiovascular diseases. However, certain ‘risk factors’ increase the risk. Risk factors include:

- Lifestyle risk factors that can be prevented or changed:

- Smoking.

- Lack of physical activity (a sedentary lifestyle).

- Obesity.

- An unhealthy diet.

- Excess alcohol.

- Treatable or partly treatable risk factors:

- Hypertension (high blood pressure).

- High cholesterol blood level.

- High trigliceride (fat) blood level.

- Diabetes.

- Kidney diseases that affect kidney function.

- Fixed risk factors – ones that you cannot alter:

- A strong family history. This means if you have a father or brother who developed heart disease or a stroke before they were 55, or in a mother or sister before they were 65.

- Being male.

- An early menopause in women.

- Age. The older you become, the more likely you are to develop atheroma.

However, if you have a fixed risk factor, you may want to make extra effort to tackle any lifestyle risk factors that can be changed.

Note: Some risk factors are more ‘risky’ than others. For example, smoking and high blood pressure cause a greater risk to health than obesity. Also, risk factors interact. So, if you have two or more risk factors, your health risk is much more increased than if you just have one. For example, a middle aged male smoker who takes no exercise and has high blood pressure has a high risk of developing a cardiovascular disease such as a heart attack before the age of 60.

Assessing (calculating) your cardiovascular health risk

A ‘risk factor calculator’ is often used by doctors and nurses to predict the health risk for an individual. A score is calculated which takes into account all your risk factors (such as age, sex, smoking status, blood pressure, blood cholesterol level, etc). If you want to know your ‘score’, see your practice nurse or GP. Current Irish guidelines advise that if your score gives you a 2 in 10 risk (or more) of developing a cardiovascular disease within the next 10 years, then treatment is advised. Treatments may include:

- A drug to lower blood pressure if it is 140/90 mmHg or higher.

- A drug to lower your cholesterol level.

- A daily low dose of aspirin. This reduces the risk of blood clots forming in the blood vessels over patches of atheroma (which cause strokes and heart attacks).

- Where relevant, to encourage you to tackle ‘lifestyle’ risk factors such as smoking, lack of physical activity, diet, and weight.

How can blood pressure be lowered?

Regular physical activity

If possible, aim to do some physical activity on five or more days of the week, for at least 30 minutes. For example, brisk walking, swimming, cycling, dancing, etc. Regular physical activity can lower blood pressure in addition to giving other health benefits. If you previously did little physical activity, and change to doing regular physical activity five times a week, it can reduce systolic blood pressure by 2-10 mmHg.

Have a low salt intake

The amount of salt that we eat can have an effect on our blood pressure. Government guidelines recommend that we should have no more than 5-6 grams of salt per day. (Most people currently have more than this.) Tips on how to reduce salt include:

- Use herbs and spices to flavour food rather than salt.

- Limit the amount of salt used in cooking, and do not add salt to food at the table.

- Choose foods labelled ‘no added salt’, and avoid processed foods as much as possible.

Eat a healthy diet

Briefly, this means:

- AT LEAST five portions, and ideally 7-9 portions, of a variety of fruit and vegetables per day.

- THE BULK OF MOST MEALS should be starch-based foods (such as cereals, wholegrain bread, potatoes, rice, pasta), plus fruit and vegetables.

- NOT MUCH fatty food such as fatty meats, cheeses, full-cream milk, fried food, butter, etc. Use low fat, mono-, or poly-unsaturated spreads.

- INCLUDE 2-3 portions of fish per week. At least one of which should be ‘oily’ such as herring, mackerel, sardines, kippers, pilchards, salmon, or fresh (not tinned) tuna.

- If you eat meat it is best to eat lean meat, or poultry such as chicken.

- If you do fry, choose a vegetable oil such as sunflower, rapeseed or olive oil.

- Low in salt.

A healthy diet provides health benefits in different ways. For example, it can lower cholesterol, help control your weight, and has plenty of vitamins, fibre, and other nutrients which help to prevent certain diseases. Some aspects of a healthy diet also directly affect blood pressure. For example, if you have a poor diet and change to a diet which is low-fat, low-salt, and high in fruit and vegetables, it can lower systolic blood pressure by up to 11 mmHg.

Drink alcohol in moderation

A small amount of alcohol (1-2 units per day) may help to protect you from heart disease. One unit is in about half a pint of normal strength beer, or two thirds of a small glass of wine, or one small pub measure of spirits.

However, too much alcohol can be harmful.

- Men should drink no more than 21 units of alcohol per week (and no more than four units in any one day).

- Women should drink no more than 14 units of alcohol per week (and no more than three units in any one day).

Cutting back on heavy drinking improves health in various ways. It can also have a direct effect on blood pressure. For example, if you are drinking heavily, cutting back to the recommended limits can lower a high systolic blood pressure by up to 10 mmHg.

Blood Tests to Detect Inflammation.

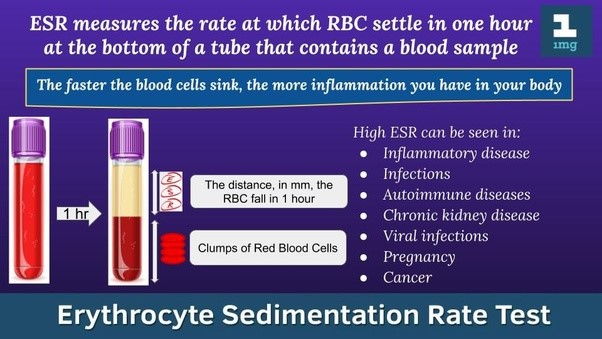

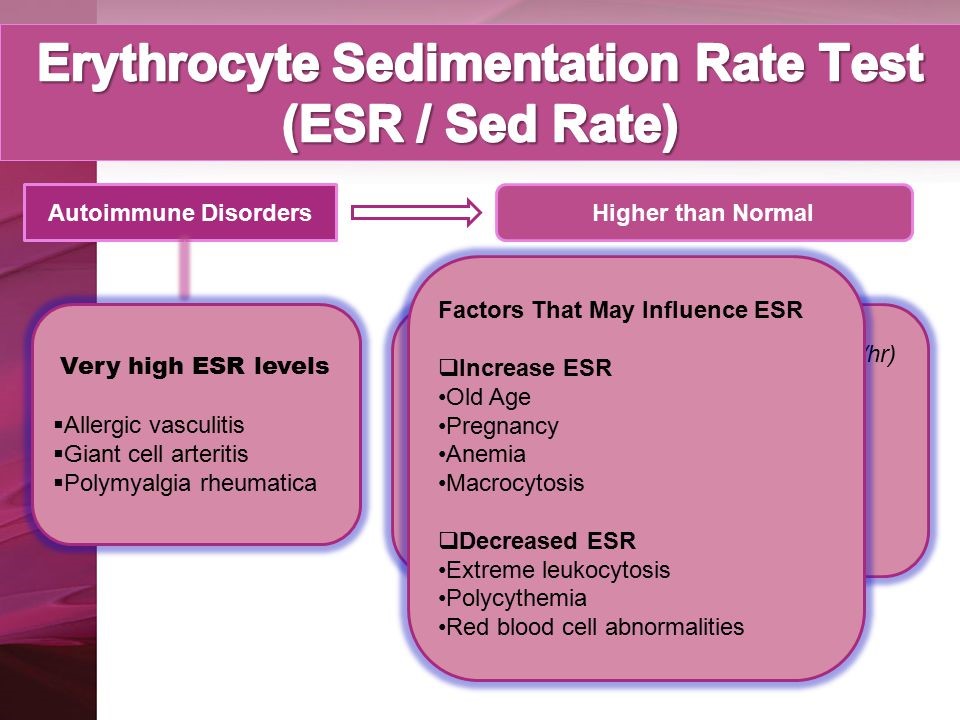

ESR are blood tests that detect inflammation. These are useful tests to help diagnose and monitor the activity of certain diseases.

Inflammation and blood proteins

If you have inflammation in a part of your body then extra protein is often released from the site of inflammation and circulates in the bloodstream. The CRP and ESR blood tests are commonly used to detect this increase in protein, and so are ‘markers’ of inflammation.

Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR)

A blood sample is taken and put in a tube that contains a chemical to stop the blood from clotting. The tube is left to stand upright. The red blood cells (erythrocytes) gradually fall to the bottom of the tube (as a ‘sediment’). The clear liquid plasma is left at the top. The ESR measures the rate at which the red blood cells separate from the plasma and fall to the bottom of a test tube. The rate is measured in millimetres per hour (mm/hr). This is easy to measure as there will be a number of millimetres of clear liquid at the top of the red blood after one hour.

If certain proteins cover red cells, these will stick to each other and cause the red cells to fall more quickly. So, a high ESR indicates that you have some inflammation, somewhere in the body.

What conditions affect the ESR and CRP level?

The ESR and CRP level are raised many inflammatory conditions. For example:

- Certain infections (mainly bacterial infections)

- Abscesses

- Certain types of arthritis

- Various other muscular and connective tissue disorders

- Tissue injury and burns

- Cancers

- Crohn’s disease

- Rejection of an organ transplant

- Heart attack

Some conditions lower the ESR. For example, heart failure, polycythaemia, sickle-cell anaemia, and cryoglobulinemia.

When are these tests used?

To help diagnose diseases

The ESR and CRP are ‘non-specific’ tests. Basically, a raised level means that ‘something is going on’, but further tests will be needed to clarify the cause of the illness. For example, you may be ‘unwell’ but the cause may not be clear. A raised ESR or CRP may indicate that some inflammatory condition is likely to be the cause.

To monitor the activity of certain diseases

For example, if you have rheumatoid arthritis, the amount of inflammation and disease activity can partially be assessed by measuring one of these blood tests. As a rule, the higher the level, the more ‘active’ the disease. The response to treatment may also be monitored as the level of CRP or ESR may fall if the condition is responding well to treatment.

Both tests are useful. However, changes in the CRP are more rapid. So, for example, a fall in the CRP within days of starting treatment for certain conditions is a useful way of knowing that treatment is working. This may be important to know when treating a serious infection or a severe flare up of an inflammatory condition. For example, if the CRP level does not fall, it may indicate that the treatment is not working and may prompt a doctor to switch to a different treatment.

Blood Tests to Detect Inflammation

Blood Tests to Detect Inflammation

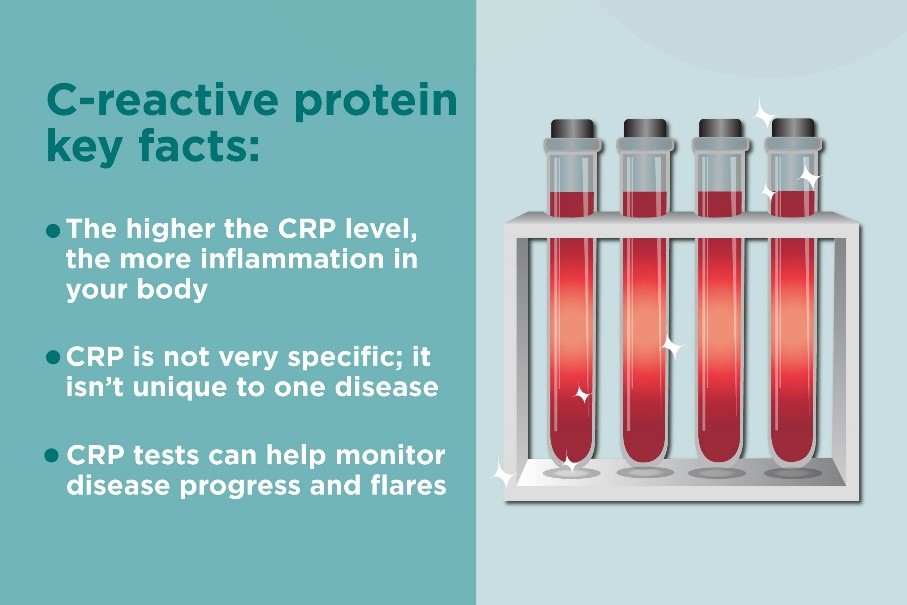

CRP are blood tests that detect inflammation. These are useful tests to help diagnose and monitor the activity of certain diseases.

Inflammation and blood proteins

If you have inflammation in a part of your body then extra protein is often released from the site of inflammation and circulates in the bloodstream. The CRP and ESR blood tests are commonly used to detect this increase in protein, and so are ‘markers’ of inflammation.

C Reactive Protein (CRP)

This is sometimes called an ‘acute phase protein’. This means that the level of CRP increases when you have certain diseases which cause inflammation. CRP can be measured in a blood sample.

What conditions affect the ESR and CRP level?

The ESR and CRP level are raised many inflammatory conditions. For example:

- Certain infections (mainly bacterial infections)

- Abscesses

- Certain types of arthritis

- Various other muscular and connective tissue disorders

- Tissue injury and burns

- Cancers

- Crohn’s disease

- Rejection of an organ transplant

- Heart attack

Some conditions lower the ESR. For example, heart failure, polycythaemia, sickle-cell anaemia, and cryoglobulinemia.

When are these tests used?

To help diagnose diseases

The ESR and CRP are ‘non-specific’ tests. Basically, a raised level means that ‘something is going on’, but further tests will be needed to clarify the cause of the illness. For example, you may be ‘unwell’ but the cause may not be clear. A raised ESR or CRP may indicate that some inflammatory condition is likely to be the cause.

To monitor the activity of certain diseases

For example, if you have rheumatoid arthritis, the amount of inflammation and disease activity can partially be assessed by measuring one of these blood tests. As a rule, the higher the level, the more ‘active’ the disease. The response to treatment may also be monitored as the level of CRP or ESR may fall if the condition is responding well to treatment.

Both tests are useful. However, changes in the CRP are more rapid. So, for example, a fall in the CRP within days of starting treatment for certain conditions is a useful way of knowing that treatment is working. This may be important to know when treating a serious infection or a severe flare up of an inflammatory condition. For example, if the CRP level does not fall, it may indicate that the treatment is not working and may prompt a doctor to switch to a different treatment.

What Is Coeliac Disease?

Coeliac disease is being diagnosed more frequently. Learn about the role of gluten in coeliac disease and how coeliac disease can be treated.

By Dr John J Ryan

Coeliac disease, also known as coeliac sprue or gluten-sensitive enteropathy, is a digestive illness that occurs due to the ingestion of gluten. If you have coeliac disease, your intestines cannot tolerate the presence of gliadin, which is a component of gluten. Gluten is present in wheat, barley, and rye. When a person with coeliac eats foods with gluten, such as bread or cereal, their immune system inappropriately reacts to the ingested gluten and causes inflammation and injury to the small intestine. This results in symptoms such as diarrhoea, bloating, and weight loss, as well as an inability to absorb important food nutrients.

“In the beginning, human beings didn’t eat any foods made with flour. We ate meat and fish, fruits, vegetables, and a small amount of different whole grains. There were no biscuits, bread, cake, or pasta,” Dr John Ryan

“The immune system in the lining of the intestine decides which items to let in and which to keep out. This human digestive and immune systems have been around for a few million years. Wheat flour as a food source has only been available for the last 7,000 to 8,000 years. For people with coeliac disease, this ‘new’ food source is not something to be tolerated but something to be reacted against,” Dr John J Ryan

Coeliac Disease: The Effect of Exposure to Gluten

The cause of coeliac disease is a combination of genes you are born with and an abnormal response of your immune system to gluten. Coeliac disease is more common in people of European descent and tends to run in families in Ireland in particular.

On a very simple level, you could think of coeliac disease as an intestinal wheat allergy. But the correct, medical way of looking at coeliac disease is “an immunologically mediated attack of the intestinal lining which occurs in certain people with a genetic predisposition to have their immune systems identify gliadin as a ‘foreign’ molecule.”

On a very simple level, you could think of coeliac disease as an intestinal wheat allergy. But the correct, medical way of looking at coeliac disease is “an immunologically mediated attack of the intestinal lining which occurs in certain people with a genetic predisposition to have their immune systems identify gliadin as a ‘foreign’ molecule.”

The result is inflammation and injury to the lining of the intestine. “This injury eliminates the ability of the intestine to absorb normal nutrients. As a result, the person with coeliac can have diarrhoea, or bloating, or failure to grow, or other consequence of the malabsorption nutrients, like iron-deficiency anaemia.

Coeliac Disease: How Common Is It?

It was once thought that coeliac disease was a rare disease that primarily affected children. As blood tests have become available to identify coeliac disease, the diagnosis is becoming more common. One out of every 133 people in Ireland has coeliac disease. In fact, coeliac disease is now one of the most commonly occurring genetic diseases in the world, and it has been estimated that 97 percent of the people with coeliac disease have not been diagnosed yet.

“Coeliac disease isn’t necessarily becoming more common. We are finally learning to recognize it and screen for it aggressively. The biggest breakthrough has been realizing that the majority of patients with coeliac, up to 80 percent, don’t have any severe gastrointestinal symptoms. They have manifestations of the disease in other ways,” Dr John J Ryan

Coeliac Disease: How Is It Treated?

“The treatment is the easiest feature, Avoid all wheat, oats barley and rye” Dr Ryan